The Edict of Thessaloniki, issued under the reign of Theodosius 1st, proclaimed Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire and officially banned paganism.

392 AD

392-500 AD

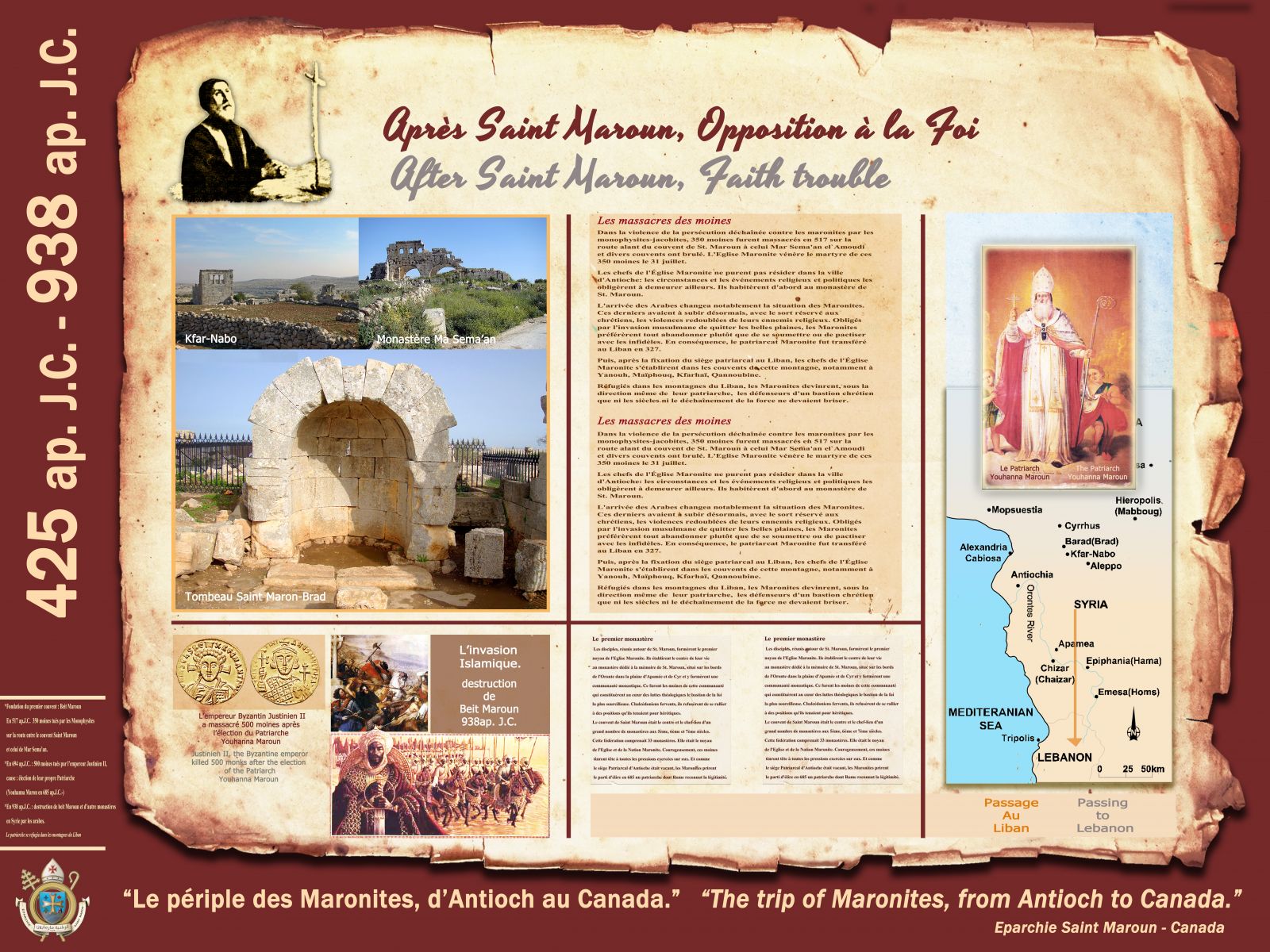

Antioch played a key role in the evangelization of Syria ”Prima” with the cities of Aleppo, Barad, Cyrus, Hierapolis and Syria “Secunda” with the cities of Apamea and Shayzar. It is also in Antioch that the term “Christian” was first used to refer to Jesus’ disciples.

392-500 AD

392-410 AD

During this turbulent period lived a monk named Maron (Maroun).

440 AD

Theodoret, bishop of Cyrus, in his Historia Religiosa written about thirty years after the death of Saint Maron in 410 AD, provides details about the life and apostolate of St. Maron.

440 AD

404AD

St. Maron escaped the chaos of the theological quarrel and retreated atop a mountain named “Nabo” to devote himself to prayer and contemplation. This outdoor ascetic life gave birth to the hermit monasticism. His exemplary life encouraged vocations and the making of disciples who dedicated themselves to the worship of God. They became more and more numerous, especially when Saint Maron left his hermitage to return among the people, who went afterwards by the name of Maronites, to preach Gospel.

350-422 AD

One of these disciples, Abraham (Ibrahim) of Cyrus, later called the “Apostle of Lebanon”, went with some companions to convert to Christianity. He then founded a community of hermits in the backcountry of Byblos, near Afka.

350-422 AD

451 AD

The Emperor Marcian united the church in the Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon, around forty years after the death of Saint Maron. The fathers, present at the Council, condemned Monophysism without ambiguity.

6th Century AD

The Emperor Marcian built an important monastery not far from the city of Apamea, known as Mar Maroun, that became the most important monastery and the great defender of the Council of Chalcedon’s teaching. The Maronite monks attracted the hostility of the Monophysites. At the beginning of the Sixth Century, the Byzantine power defended the monophysites. Thus, the monophysite Patriarch Severus of Antioch, with the support of the Emperor Anastasius, went to persecute the Chalcedonians and, at the head of the list, the monks of Mar Maroun.

6th Century AD

517 AD

637 AD

The Maronites found refuge in Baalbek, Acre and the cities of the Phoenician coast, up to Byblos, a city that did not interest the Arabs. In addition, they took shelter in hard-to-reach places and managed to survive. The Maronites even carried out attacks against the invader with the help of the Maradas from Taurus, Aramaic speakers and of Chalcedonian faith like them.

637 AD

685 AD

The patriarchal seat was vacant, the Chalcedonians of the Church of Antioch elected their patriarch, Jean-Maron (Youhanna Maroun), a Maronite monk and bishop of Batroun, without referring to Constantinople.

694 AD

The Maronites were able to resist the Byzantine army and inflict on it a crushing defeat. Youhanna Maroun was elected to the patriarchal seat and officially consecrated the Maronite Church.

694 AD

938 AD

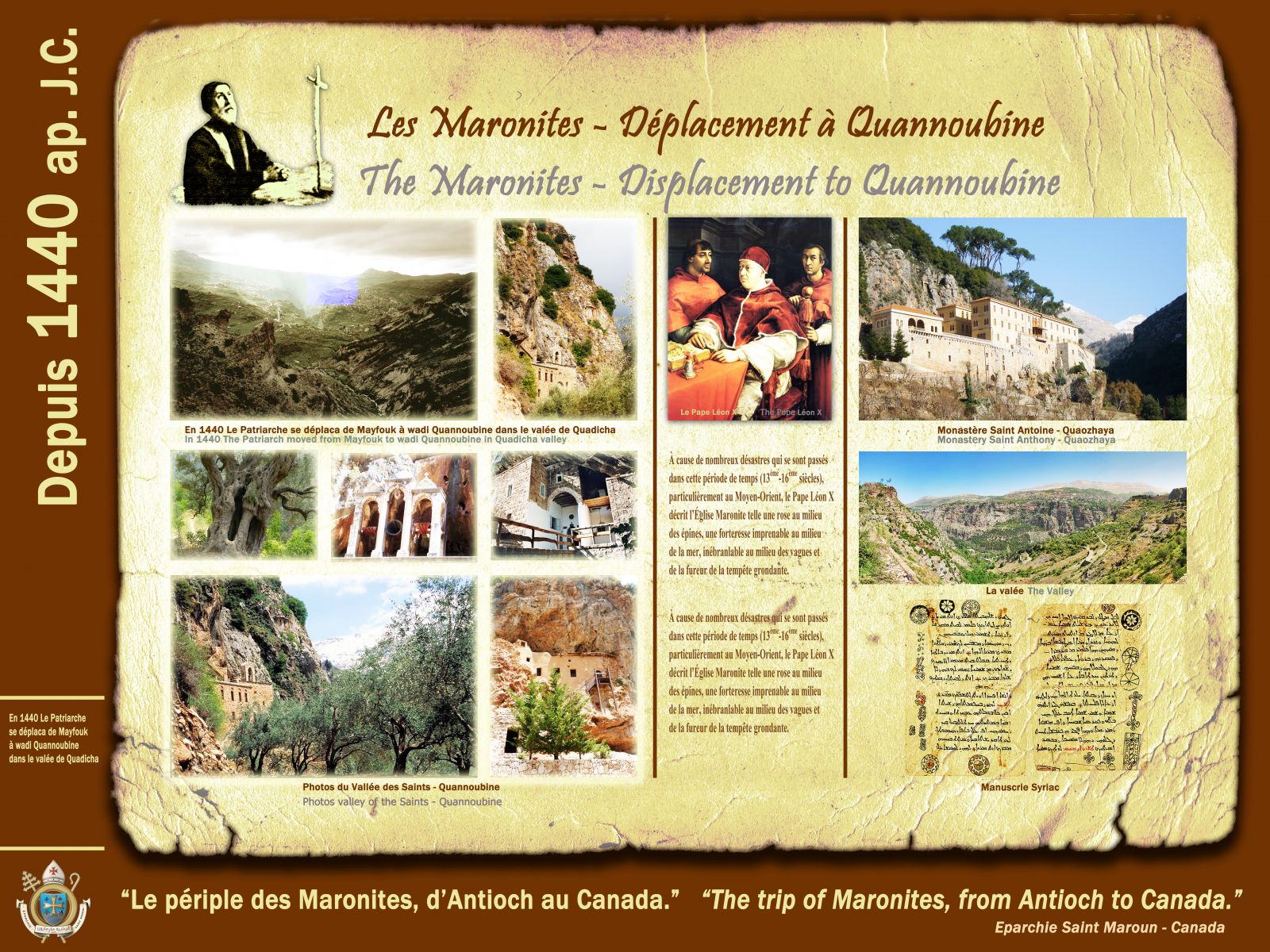

After the destruction of the Maroun monastery by the Arabs, the patriarchal siege was definitively established in Lebanon to escape the disorders which afflicted the countries of the East and which opposed the Byzantines, Seldjukides and Fatimids until the arrival of the Crusaders in 1098 AD.

1215 AD

During the presence of the Crusaders in the East, the Patriarch Jeremiah of Amchit visited Pope Innocent III and took part in the Lateran Council. The thirteenth Century was that of the blossoming era of the Maronites. Enjoying the protection of the Crusaders, they were able to proclaim their faith without fear and to built many convents and churches.

1215 AD

1291 AD

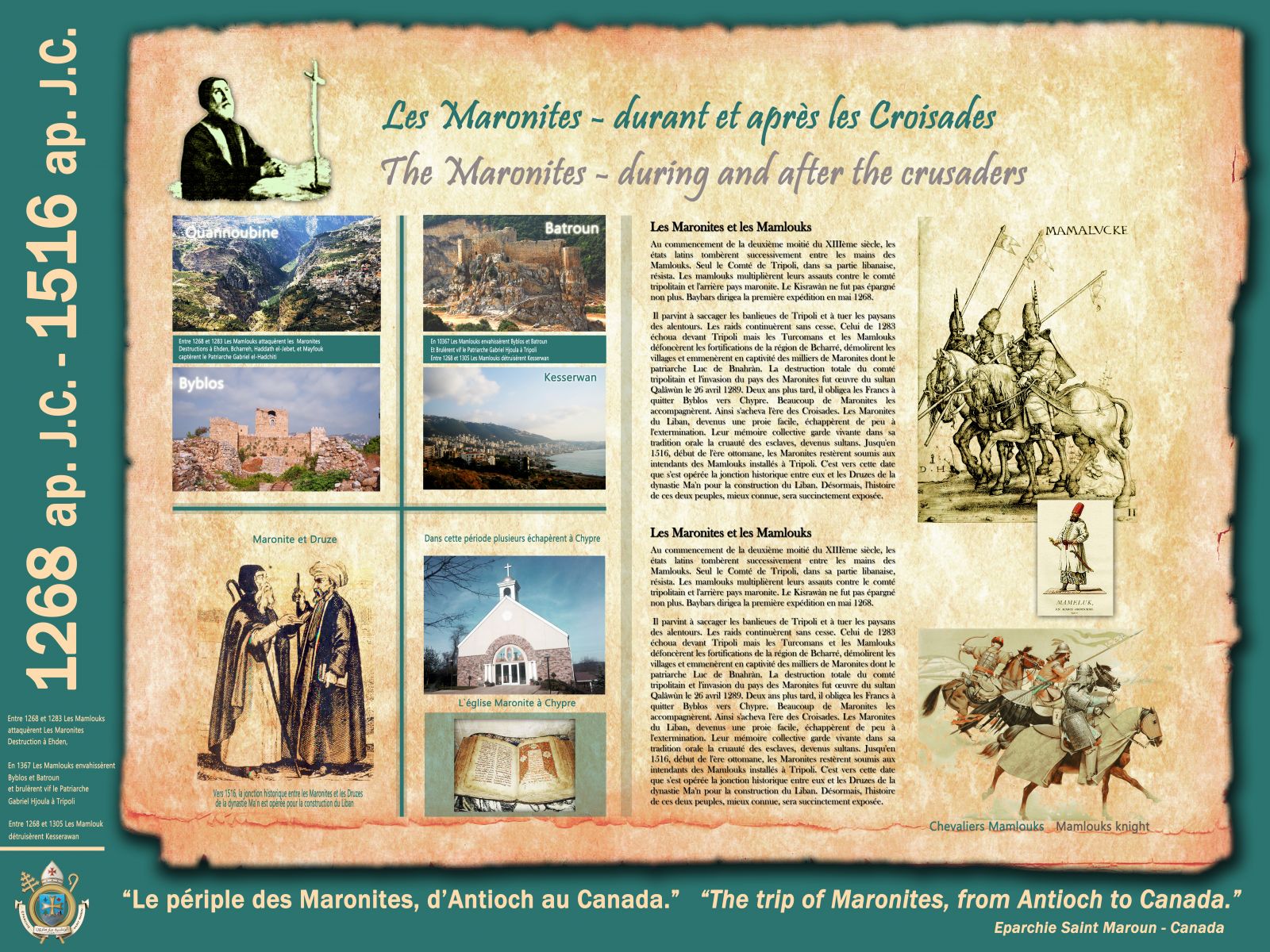

The Mamelukes took Tripoli back from the Crusaders and put an end to their presence on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean. Several Maronites left with the Crusaders for Cyprus, where they established a community that exists to this day. This was the first wave of Maronite emigrants leaving Lebanon. An estimated fifty thousand Maronites died for the defense of the cross.

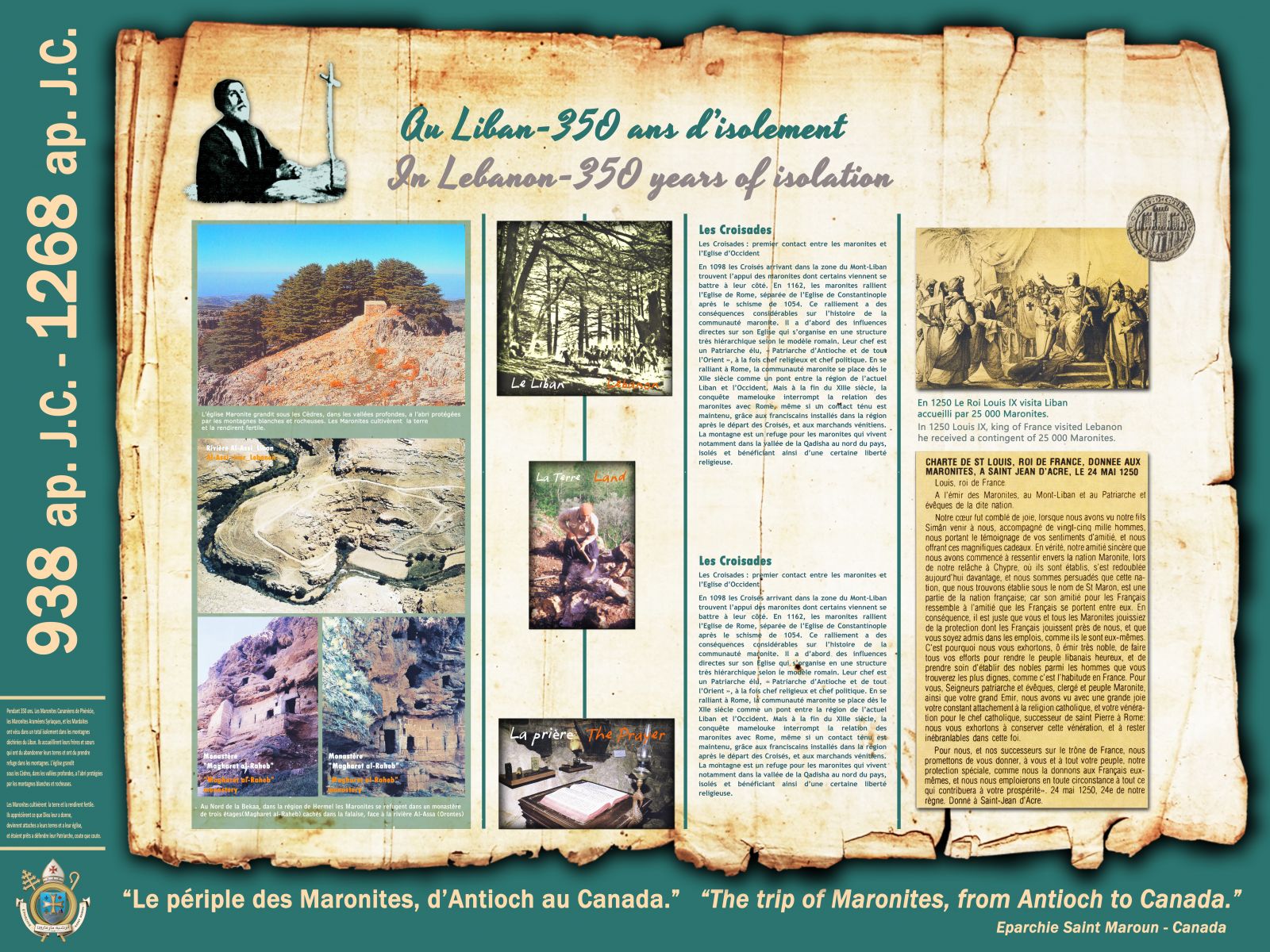

1250 AD

After the departure of the Crusaders, the Maronites suffered from the violence of the Mamelukes from Egypt, of which they became masters in 1250 AD. The Mamelukes, before and after the departure of the Crusaders, led many murderous raids against the Maronites. The Mamelukes waged wars and group massacres. Those who escaped the massacre were deported: the Nosaïris to Akkar, the Druze to Chouf and the Shiites to the South. The vacant land thus created in Keserwan allowed the Maronites to settle there without disturbing the Mamelukes. This is how the Maronite population gradually expended to the entire mountain.

1250 AD

1516 AD

The Ottoman rule over Lebanon began with Sultan Selim the First, known as the Cruel, who, in two years’ time, had conquered Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, and brought no change to the feudal structure or social organization of the Lebanese mountain. His successor, Soleiman the Magnificent, confirmed the right of the Maronites to manage their own affairs and their Patriarch was the only person not subjected to the obligation to see his investiture confirmed by the Sultan.

1860 AD

The Turks disarmed the Christians and encouraged the Druze to massacre them. At least ten thousand Maronites died. During Pope Gregory’s reign, The Maronite School of Rome was built in 1584. This school was concerned with the development of the Maronite clergy who played an important role in the evolution of the Lebanese society.

1860 AD

1610 AD

The clergymen introduced the first printing plant in the East and installed it in the convent of Kozhaya. The Maronite School of Rome also graduated forty bishops, of whom twelve became patriarchs. The most famous, Patriarch Douaihy, he was the first historian of his church. In addition, the school enabled the Maronites to emerge from their intellectual isolation and to be in permanent contact with the Western thought, while waiting to be the main architects of the revival of the Arabic language and literature.

1305 AD

The demographic expansion of the Maronites began in Keserwan, following the massacre and the deportation of its Shiite, Druze and Nosai populations by the Mamelukes, and continued towards Metn and Chouf. This migration has led the Maronites to cohabit with other communities and to experience cultural and religious diversity. As tensions existed between Sunnis, Shiites and Druze, the Maronites were led to play the role of mediators and interpose themselves among themselves.

1305 AD

1831 AD

A meeting was held at Mar Elias Church-Antelias between the Druze, Sunni, Maronite and Shiite representatives. They took the oath to fight together against Ibrahim Pasha who had just invaded Lebanon at the head of an Egyptian army. They succeeded in repelling him. With them, fought a seventeen-year-old Maronite, Youssef Beyk Karam, who later became famous for his fight against the Ottomans.

1918 AD

All the Lebanese communities asked Patriarch Hoayek to represent them at the Versailles conference and to demand the independence of Lebanon.

1918 AD

Emperor Constantine convoked an ecumenical council at Nicaea in 325 AD and granted Christianity an important role in the proper functioning of the Roman Empire. This historic decision, highly momentous for the unity of the empire and for the control of politics and religion by the state, was preceded and prepared by the Edict of Milan issued in 313 AD, which granted freedom of religion and, theoretically, put an end to abuses and persecution that targeted the Christians. Meanwhile, Constantine founded, on the western shore of the strait that separates the Aegean Black Sea from the Black Sea, a city that bears his name: Constantinople. The latter played a very important role in the fate of Eastern Christians.

It was only in 392 AD, with the Edict of Thessaloniki, under the reign of Theodosius, that the Christian religion became the Empire’s official religion and that paganism was officially banned. Upon the death of Theodosius, the Roman Empire was divided into two parts: The Western Empire with Rome as its capital, and the Eastern Empire with Constantinople as its capital. The first would keep Latin as the official language, and the second would become the Byzantine Empire and would adopt the Greek language.

The decision of Theodosius to make Christianity the official religion of the Empire did not have a direct effect on the entire population or regions. Several areas remained resistant, especially those far from urban centers and means of communication. This was the case of the Lebanese mountain which remained very attached to the old cult and had an impressive number of temples in honor of the Phoenician divinities. On the other hand, the coastal towns had already had their churches long time before. Indeed, the first “nice” disciples of Christ date back to the time when Jesus was preaching in Galilee, just south of the Phoenician coast, and was going with His mother to the neighboring villages and towns such as Qana, Tyre and Sidon. After the death of Christ, the Apostles, answering his desire to “make disciples of all nations,” began their apostolate by heading north along the Eastern Mediterranean and established churches in Tyre, Sidon, Berytus, Byblos, Tripoli and Antioch. Antioch soon became an important spiritual center through the apostleship of Paul and Barnabas.

Along with Constantinople, Alexandria, Jerusalem and Rome, Antioch had the privilege of being one of the five patriarchal sites. Antioch played a key role in the evangelization of Syria “Prima” with the cities of Aleppo, Barad, Cyrus and Hierapolis, and Syria “Secunda” with the cities of Apamea and Shayzar. It is also in Antioch that the disciples were first called Christians. Unfortunately, the city did not escape the theological disputes that had agitated the Church about the nature of Christ. On one hand, were those who believed in the dualistic nature of Christ, human and divine, and on the other hand,

were the Monophysites who only recognized the divine nature of Christ. These disputes were not limited to arguments; they degenerated more often into extreme violence. It was during this turbulent period, torn by fratricidal battles, that would have lived a monk named Maron (Maroun).

The only written testimonies we have about the life and apostolate of Saint Maron, are from Theodore, bishop of Cyr. In his Religious History of Syriac Asceticism, written about thirty years after the death of Saint Maron in 410 AD (year of the sack of Rome by Alaric, King of the Visigoths), he refers to more details about the life and apostolate of the Saint. His life was so exemplary and his fame so great that Saint John Chrysostom sent him, from his exile around the year 404 AD, a letter to show him respect and ask him to intercede for him in his prayer. Probably to escape the chaos of the theological quarrel, Saint Maron retreated atop a mountain named “Nabo” to devote himself to prayer and contemplation. This outdoor ascetic life would have encouraged many emulators and had given birth to solitary monasticism. Indeed, the exemplary life of Maron, dedicated in extreme poverty to prayer and God, quickly encouraged vocations and preparations of disciples who isolated themselves in caves or on mountaintops to devote themselves to the example of their master, to the worship of God. They became more and more numerous, especially when Saint Maron had left his hermitage to return among the people to preach the Gospel and went afterwards by the name of Maronites.

One of these disciples, Abraham (Ibrahim) of Cyr (350-422 AD), later called the “Apostle of Lebanon”, headed with some companions, with some difficulties, to the Lebanese mountains to convert to Christianity. He then founded a community of hermits in the backcountry of Byblos near Afka where Adon river rises. Consequently, the river’s name was changed to what we know as Nahr Ibrahim. During this period, the conversion of the Lebanese Mountain’s population to Christianity began and continued. This land became the refuge of the apostles.

The Council of Chalcedon

The religious quarrels having not ceased, and having become a danger to the unity of the Church, the Emperor Marcian united the fourth ecumenical council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, forty years after the death of Saint Maron. The fathers present at the Council condemned Monophysitism without ambiguity.

“We all unanimously teach that our Lord Jesus Christ is to us One and the same Son, the Self-same Perfect in Godhead, the Self-same Perfect in Manhood; truly God and truly Man; the Self-same of a rational soul and body; co-essential with the Father according to the Godhead, the Self-same co-essential with us according to the Manhood; like us in all things, sin apart…” (Dogmatic Definition of the council of Chalcedon 451AD)

Unfortunately, the council did not succeed in putting an end to quarrels. It distinguished, and up to the present day, the Chalcedonians from the Monophysites: The Chalcedonians with the Pope and the Western Church, the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Byzantine Greeks, the Greek Catholic Melkites, the Orthodox Greeks and the Maronites; and the Monophysites with the Coptic Church of Alexandria, the Ethiopian Church, the Armenian Gregorian Church and the Orthodox Syriac Church.

Anxious to defend the Chalcedonian faith, the Emperor Marcian built an important monastery not far from the city of Apamea.

Known as Mar Maroun, this monastery became the most important of the monasteries and the great defender of the teaching of the Council of Chalcedon. By the zeal in propagating their faith, the Maronite monks attracted the hostility of the Monophysites. At the beginning of the Sixth Century, the Byzantine power has changed sides and, for a time, defended the Monophysites. Thus the monophysite Patriarch Severus of Antioch, with the supported of the Emperor Anastasius, went to persecute the Chalcedonians and, at the head of the list, the monks of Mar Maroun. In 517 AD, 350 Maronite monks, who went to an alleged meeting of reconciliation with the Monophysites, were ambushed and massacred.

In spite of this massacre and despite the religious incoherence of Byzantium, the Maronite Church retained its Chalcedonian faith, remained attached to the magisterium of the universal Church and showed unfailing fidelity to the successors of Peter. It is from these constants that the Maronite soul was shaped and established.

The Arab invasion of Syria and Lebanon

The invasion began with the fall of Damascus in 635 AD. Two years later, in 637 AD, Baalbek, Acre and the cities of the Phoenician coast up to Byblos were already occupied. However, the mountains did not interest the Arabs; therefore, the Maronites found refuge there. Taking shelter in hard-to-reach places, they managed to survive. They even carried out attacks against the invader with the help of Maradas from Taurus, who spoke Aramaic like them and were of Chalcedonian belief. They were recruited by the Emperor of Byzantium to attack the Arab armies and curb the expansion of the Umayyad Empire. The courage and boldness of these allies enabled them to strongly retaliate.

Caught between great empires and the interests that surpassed them, the Maronites were once again subjected to the inconstant Byzantine politics. Unknown to them and unknown to the Maradas, the Basileus autokrator (the name of the emperor since 630 AD) concluded with the Khalif, with some material advantages, an agreement that put an end to military activities of the army Marada-Maronite. This decision had very serious consequences for the future of the Christians of the East.

It was also at this time, around 638 AD, that the theological quarrel in the Chalcedonian camp between those who claimed that Christ, although having two natures, had only one divine will and those who affirmed that He had two natures and two wills, divine and human.

At the Council of Constantinople in 680 AD, Monothelitism, in other words the affirmation of the single will, was condemned. Some sources reported that the Maronites were at one time monotheists. In conclusion, the Council did not designate the Maronites and the accusation today lacks irrefutable evidence.

Jean-Maron, first Patriarch of Antioch (685AD)

Tired of the incoherence of Byzantine politics, and finding that the patriarchal seat was vacant, the Chalcedonians of the Church of Antioch elected, in 685 AD and without referring to Constantinople, their patriarch, Jean-Maron (Youhanna Maroun), a Maronite monk and bishop from Batroun and Mount Lebanon. This decision of great historical significance for Lebanon constituted the official consecration of the Maronite Church.

Tired of the incoherence of Byzantine politics, and finding that the patriarchal seat was vacant, the Chalcedonians of the Church of Antioch elected, in 685 AD and without referring to Constantinople, their patriarch, Jean-Maron (Youhanna Maroun), a Maronite monk and bishop from Batroun and Mount Lebanon. This decision of great historical significance for Lebanon constituted the official consecration of the Maronite Church.

Basileus regarded this election as an act of insubordination which would affect his imperial authority. He sent an army to capture the patriarch who had established his residence at the Mar Maroun convent on the Orante. Youhanna Maroun managed to escape the army of Basileus and took refuge in the region of Byblos. The convent was destroyed and five hundred monks were found dead.

Retired in the Lebanese mountain with their patriarch, the Maronites resisted the Byzantine army and won a decisive victory in 694 AD. The two commanders of the imperial army were killed in this battle. Just as the election to the patriarchal seat of Youhanna Maroun officially consecrated the Maronite Church, this victory marked the birth of the Maronite nation. The English historian Edward Gibbon of the Eighteenth Century wrote: ”Maronite was transferred from a hermit to a monastery, and from a monastery to a nation. This humble nation survived the empire of Constantinople, which persecuted it”.

After this episode, the Maronite Patriarchs spent their time between the convent of Kfarhaï in Lebanon and the reconstructed convent of Mar Maroun on the Orante. It was not until 938 AD, after the destruction of the Maroun monastery by the Arabs, that the patriarchal siege was definitively established in Lebanon to escape the disorders which afflicted the countries of the East and opposed the Byzantines, Seldjukides and Fatimids, until the arrival of the Crusaders in 1098 AD.

Persecuted by the Muslims as well as by their Byzantines, the Maronites, despite their small number and poverty, showed remarkable pugnacity when it came to defending their identity and their faith.

The crusaders

At the Council of Clermont in 1095 AD, Pope Urban II conceived the idea of resuming the Holy Sepulcher and rescued Jerusalem from Muslim occupation. For about two centuries (1098-1292 AD), the west organized several military expeditions to reconquer the Holy places and defended the kingdoms, principalities and counties that the Crusaders had established along the Mediterranean coast. One of them, the kingdom of Jerusalem strengthened the ties with the county of Tripoli, the principality of Antioch and the kingdom of Cyprus, which directly concerned the Maronites.

Apart from a few incidents, the relation between the Maronites and the Latins was excellent. As soon as they arrived in the Orient, the Crusaders received a spontaneous and immediate help from the Maronites, who in turn enjoyed special protection and privileges. Louis IX, king of France, went as far as to declare that the Maronite nation was part of the French nation, recommended it to his successors and exhorted the Maronites to remain faithful to the successor of Peter.

The Holy See, who thought that the Maronites had disappeared, was happy to learn that they still existed. The official links were quickly established and consolidated; the Maronites asserted their loyalty to the Pope as soon as the Crusaders had arrived.

It was during the presence of the Crusaders in the East that the Patriarch Jeremiah of Amchit visited Pope Innocent III in 1215 AD and took part in the Lateran Council. The Thirteenth Century was the blossoming era of the Maronites. Enjoying the protection of the Crusaders, they were able to proclaim their faith without fear of reprisals and saw their material conditions improve. They took the opportunity to build many convents and churches.

The departure of the Crusaders

In 1291 AD, the Mamelukes took back Tripoli from the Crusaders and put an end to their presence on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean. Several Maronites left with the Crusaders to Cyprus, where they established a community that exists to this day. This was the first wave of Maronite emigrants leaving Lebanon. An estimated fifty thousand Maronites died for the defense of the cross. Despite a negative military record, the crusades had the merit of re-establishing contacts between the West and the East, of initiating a trade movement which would continue to increase during the Italian Renaissance in the quattrocento and the cinquecento. This new reality could only serve the Maronites, whose ties with the West and Rome would have never been broken again.

The tyranny of slaves who have become kings, the Mamelukes

After the departure of the Crusaders, the Maronites witnessed the violence of the Mamelukes (slaves) who had become soldiers and a powerful military oligarchy. All the way from Egypt, which they ruled in 1250 AD, they conquered Lebanon and Syria and retained power until 1517 AD, when they were defeated and replaced by the Ottomans. Unlike the Arabs who saw no military interest in the Lebanese mountain, the Mamelukes, in their struggle against the Crusaders, realized the strategic importance of the mountain and understood that it was first necessary to reduce their entrenched Maronite allies in hard-to-reach places from which they would undertake surprise attacks. The Mamelukes, before and after the departure of the Crusaders, led many murderous raids against the Maronites. Several Patriarchs were humiliated and killed. One of them, Gabriel de Hejoulah, was even burnt alive in Tripoli in 1367 AD. It is said that there is not more crueler than a slave who has become king. The Mamelukes were very violent and massacred a large number of Maronites.

Despite all the misfortunes and suffering endured, the survivors were able to regroup and rebuild their community life around their patriarchs. They have even succeeded in securing relative autonomy and experienced population growth through a very high birth rate. The Maronites were not the only victims of the Mamelukes’ cruelty. Other communities, which belonged to Islam, were persecuted and found refuge in the Lebanese mountain. This was the case of the Nosairis, the Shiites and the Druze who had settled in Keserwan.

Taking advantage of the wars between Mamelukes, Crusaders and Mongols, these communities revolted against their oppressors. The Mamelukes, who had just forced out the Franks and the Mongols, turned against the insurgents of Keserwan, and quickly materialized their revolt. Repression and vengeance were terrible. Those who escaped the massacre were deported: the Nosaïris to Akkar, the Druze to Chouf and the Shiites to the South. The hub thus created in Keserwan allowed the Maronites to settle there without disturbing the Mamelukes.

This is how the Maronite population’s expansion gradually reached the entire mountain and created a new reality: the cohabitation and organization of intercommunity relations became both a wealth for Lebanon and a unique experience of conviviality and intercultural dialogue. However, at the same time, it can be considered as an Achilles heel, that allows the occupants to divide and rule them.

The Sublime Gate

The Ottoman rule over Lebanon began in 1516 AD with Sultan Selim the First, known as the Cruel, who, in two years’ time, had conquered Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, and brought no change to the feudal structure or social organization of Mount Lebanon.

His successor Soleiman the Magnificent confirmed the right of the Maronites to manage their own affairs and their Patriarch was the only one not subject to the obligation to see his investiture confirmed by the Sultan.

This generous attitude towards the Maronites was perhaps not entirely gratuitous. Francis First, king of France, in struggle with the Habsburgs of Austria who were ruling over the Holy Roman Germanic Empire, had drawn nearer to their enemy Soleiman the Magnificent and had obtained in 1535 AD, an agreement called “Capitulation” on the status of Foreigners and Christians living in the Levant. This closeness suited perfectly the “Great Lord” who coveted the territories of the Habsburgs. For his part, Francis First found doubly his account in Europe against the Habsburgs and in the East where he and his successors would have a gateway and a pretext to intervene. The Maronites could only rejoice and enjoy this agreement.

Unfortunately, the Ottoman domination had often been a source of misery and misfortune for the Maronites who experienced hardships during this dark period. For example, In 1860 AD, the Turks disarmed the Christians and encouraged the Druze to massacre them, where at least ten thousand Maronites died. During the First World War, Turkey allied with Germany and made a food blockade, preventing food from reaching the inhabitants of the mountain. Hundreds of thousands of people died of hunger. To this incident, the arrogant and arbitrary behavior of the occupier, the vexatious measures, the corruption of the administration, the unjust seizure of properties and many more difficulties must be added.

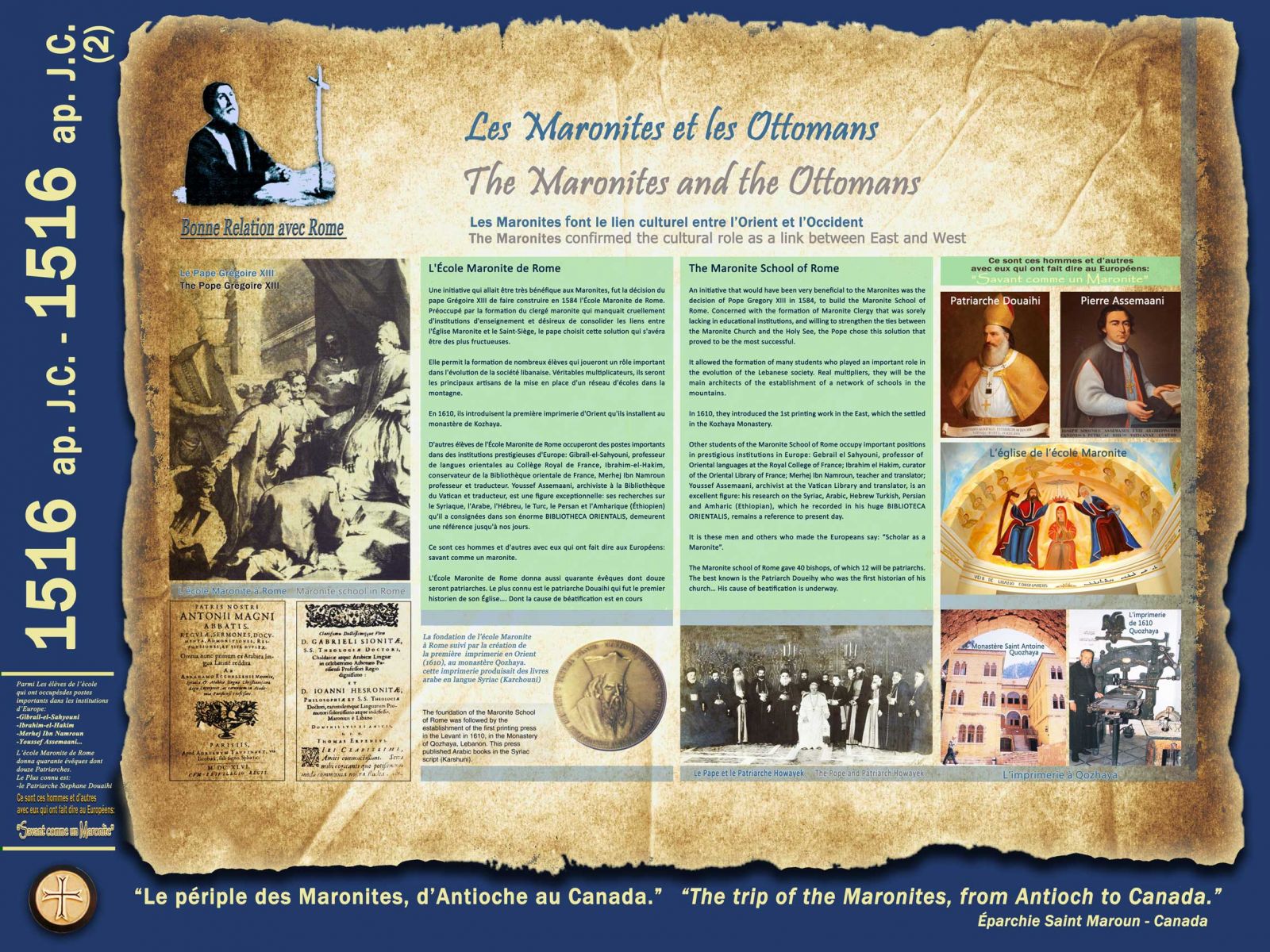

An initiative that proved to be very beneficial to the Maronites was Pope Gregory XIII’s decision to build the Maronite School of Rome in 1584 AD. He was concerned with the quality of instructions given to the Maronite clergy and, because of the lack of educational institutions, he wanted to consolidate the ties between the Maronites and the Holy See. For all of these reasons, the Pope decided to build the school which proved to be one of the most fruitful solutions.

The Maronite School in Rome enabled the development of many pupils who played an important role in the evolution of the Lebanese society. These pupils, who were truthful multipliers, were the main architects of the establishment of a network of schools in the mountains.

In 1610 AD, they introduced the first printing plant of the East and installed it in the convent of Kozhaya. Other students of the Maronite School of Rome held important positions in prestigious institutions in Europe: Gibrayil El-Sehnaoui, professor of Oriental languages at the Royal College of France, Ibrahim El-Hakim, Curator of the Oriental Library of France , Merhej Ibn Namroun, professor and translator. Youssef Assemaani, archivist at the Vatican Library and translator, was an outstanding figure. His research on Syriac, Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, Persian and Amharic (Ethiopian) that he would have recorded in his enormous Bibliotheca Orientalis remains a reference to this day. These men, as well as others, made the Europeans coin the following expression: “knowledgeable like a Maronite.”

The Maronite School of Rome also graduated forty bishops, of whom twelve were patriarchs. The most famous one, Patriarch Douaihy, was the first historian of his church.

From the Seventeenth Century onwards, Latin religious communities supported the Maronite clerics in their educational mission: the Capuchins in 1626 AD, the Carmelites in 1635 AD, and the Jesuits in 1656 AD. Later on, other communities also followed the same path.

The Maronite School of Rome enabled the Maronites to emerge from their intellectual isolation and be in permanent contact with western thought, while waiting to be the main architects of the revival of Arabic language and literature. It also triggered, in Maronite society, an acute awareness of the importance of education. The Lebanese synod held at Louaizé in 1736 AD affirms: ”In the name of Jesus Christ, we exhort the ordinaries of the dioceses, towns, villages, and convents to help each other to encourage this work which has been very fruitful. They must find a teacher where there is none, write the names of the children who are able to learn, order the parents to bring their children to school. If they are poor or orphans, the church or convent gives them food and if the church cannot, it gives a part and the parents give another. ”

This decision was remarkable when one considers the time at which it was made. It made all parents consider their children’s education a top priority. One of the greatest pride of the Maronites in the construction of modern Lebanon is the creation of schools. They have been open to all communities and have enabled Lebanon to become a center of intense cultural activity.

The revival of the language, literature and of the Arabic thought took off in Lebanon.

The experience of conviviality or a Plural Society

The demographic expansion of the Maronites began in Keserwan following the massacre and deportation of Shiite, Druze and Nosai population in 1305 AD by the Mamelukes, and continued towards Metn and Chouf. This migration has led the Maronites to cohabit with other communities and to experience cultural and religious diversity.

As tensions existed among Sunnis, Shiites and Druze, the Maronites were led to play mediators and interpose themselves among themselves. With time and common trials, a feeling of conviviality and belonging to the same land had developed. The whims and severity of the Ottoman occupation have made this pluralistic population conscious of a common destiny. Several moments in the history of Lebanon illustrated this new reality. The reign of Fakhreddin II (1572-1635 AD) a Druze emir, and that of Bechir II (1789-1840 AD) a Sunni emir converted to Christianity, testify to a mobilization of all communities against the occupier. Another significant example of this inter-communal solidarity was the meeting in 1832 AD at the Mar Elias Antelias church, held between the Druze, Sunni, Maronite and Shiite representatives. They took the oath to fight together against Ibrahim Pasha who had just invaded Lebanon at the head of an Egyptian army. They succeeded in repelling him. With them, fought a seventeen-year-old Maronite, Youssef Bek Karam, who later became famous for his struggle against the Ottomans. After the defeat of Turkey in 1918 AD, all the Lebanese communities asked Patriarch Hoayek to represent them at the Versailles conference and to demand the independence of Lebanon.

By opting for Greater Lebanon, the Patriarch clearly demonstrated the will of the Maronites to live in peace and harmony with other communities.

There were also, and unfortunately, in this experience of conviviality, very serious accidents such as the massacres of 1860 AD, the troubles of 1958 AD and the war of 1975 AD. The latter devastated the country and threatened intercommunity links, divided the flaws and almost took Lebanon away.