Maronite hymns, origins and evolution

The origins of the Maronite Church hymns are closely related to those of the Church of Antioch, direct heiress of Jerusalem. The first Christian Antiochian community was born in a Jewish environment. This assembly, closely linked to the synagogue, was inspired in its collective prayer of Jewish traditions: readings of the Old Testament to which are added extracts of the New Testament, hymns of psalms and biblical canticle. But soon, the Church emerged from its Jewish context and developed according to her own cultural mode.

New traditions were born, inspired hymnologists enriched the Church, either by adopting melodies and forms inspired by the Jewish tradition, such as the psalms, or by popular hymn, or by composing new melodies and new forms. At the 1st century, we find traces of these forms, for example in the Letters of St. Paul or in other writings of the New Testament.

Interweaved with Roman, Byzantine and Jewish influences, the Antiochian tradition saw the birth of a new element in the fourth century: the Syriac hymnody of Edessa represented especially by Saint Ephrem of Edessa (306-373).

As St Ephrem states, as early as the 2de century, Bardesan (154-222) composed hymns through which he propagated his ideas and doctrines; Harmonius, his son, took care to give them beautiful melodies that he composed or adapted from an older repertoire. Texts and melodies were so well composed that they delighted the listeners and diverted them from the orthodox doctrine.

When Saint Ephrem saw the taste of the inhabitants of Edessa for the hymns, he instituted in exchange for the young people games and dances. He established choirs of virgins to which he had hymns divided into stanzas and choruses. He put into these hymns delicate thoughts and spiritual instructions on the Nativity, on baptism, fasting and the acts of Christ, on the Passion, the Resurrection and Ascension, as well as on the confessors, penance and the dead. The virgins reassemble on Sundays, at great festivals and at the commemoration of the martyrs; and he, like a father, stood in the middle, accompanying them with the harp. He divided them into choruses for alternating melodies and taught them the different musical tunes, so that the whole city gathered around him and the opponents were shamed and disappeared.

With the Crusaders, 10th – 12th century, the Maronites began to adopt usages and rites of the Roman Church; it was the first attempt of Latinization. But by introducing modifications into the text of the liturgy, they most often sought to adapt them to the rules of the ancient antiochian rite. A second attempt of Latinization took place in the 16th century with Western missionaries and the founding of the Maronite College of Rome (1584-1808).

In spite of all these trends towards Westernization, Maronite singing could save its characteristics. Moreover, we do not find any name of a Maronite composer, or any musical transcription of traditional Maronite hymns before the end of the 19th century. Translations or compositions of hymns in Arabic were started in the first half of the 18th century, especially with Abdallah Qarali (1672-1742) and Germanos Farhat (1670-1732), and in the second half of the same century with Youssef Estephan (1729-1793); but it was always in the spirit of tradition, respecting the characteristics of traditional liturgical chant.

Maronite hymn, forms and classification

Syriac melody is made mostly of a much diversified hymnology where one can distinguish the following forms:

In traditional Maronite music, as in all ancient music, the voice holds the first place and the instruments serve to accompany the voice. For this reason the rhythm of poetry almost always regulates that of music. Maronite chant in general is monodic, almost always strophic and syllabic. The range of melodies is limited: they proceed by joint movement, the modality is of an archaic type and the rhythm is varied.

At this point, we can divide the musical repertoire of the Maronite Church into 5 groups:

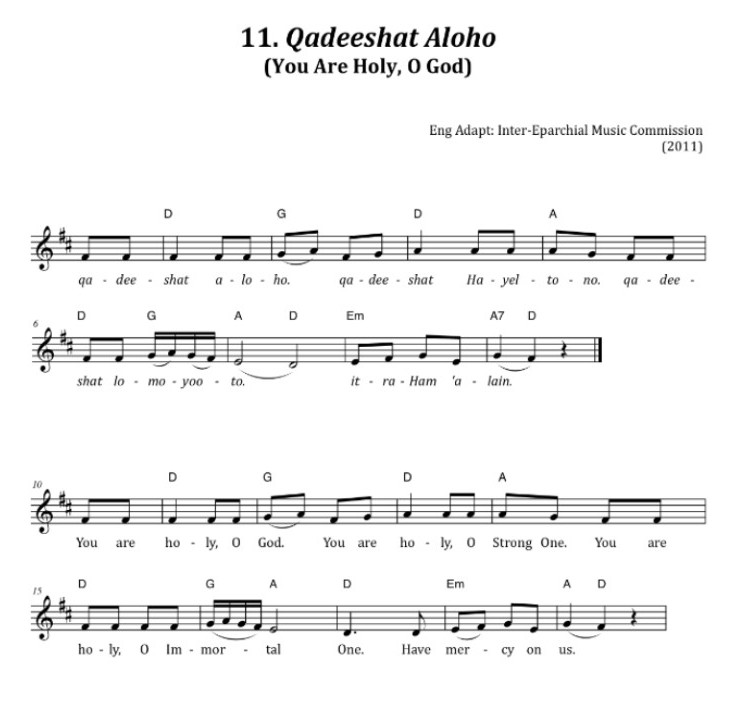

- The Syro-Maronite hymn whose melodies are very old and the text is in Syriac language.

- The Syro-Maronite Arabic hymn whose melodies are those of the Syro-Maronite hymns but the text is in Arabic language.

- Improvised melodies.

- Foreign melodies. These are oriental or western melodies applied to Arab texts from the 18th century or so.

- The personal melodies. This group was born at the end of the 19th century. It presents a very wide variety.

On the linguistic level, the Maronites spoke Syriac, which was the official language of the region until the Arab conquest in the 7th century. From the 7th century, the Syriac language is competing with the Arabic language, which ends up replacing it in the conquered countries. The crossing of these two languages was born in Lebanon what is called the Lebanese dialect.

So the liturgical language of the Maronites was Syriac until the 16th century. Since then, Arabic is added to the liturgical texts.

Extract from a published article

Prepared by Father Miled Tarabay 2006